EFAO spoke with four farmers leading three unique farming and land stewardship operations in Ontario to find out how their personal histories, philosophies and experiences have influenced their approaches to farming.

Cady & Alvis operate Deeper Roots Farm, a two person team operating in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), focusing solely on cultural appropriate heirloom varieties, growing organically, saving seeds and using traditional growing practices.

Arlene Meekis-Jung of Wawakapewin, of the Oji-Cree First Nation reserve (Kenora district), operates a market garden community farm in a remote Northern community (Kenora District) with only float plane access, 350 km north of Sioux Lookout.

Judith “ZhiiZhii” Prince grows food as part of her work with the Ubuntu Community Collective, which is focused on serving women and children of the African diaspora.

How does farming connect You With Your Roots? Who or what has been your biggest inspiration?

Beet harvesting at Deeper Roots Farm.

Cady: My great grandfather is my greatest role model. He managed at least two acres of land on his own and was able to feed my family every day. There was no need to go to the grocery store except to get imported goods like flour. I’ve also learned of other family members who also were farmers. The more I learn, the more I feel as though life has nudged me into farming.

Alvis: Elliot Coleman. The way he championed education for small scale farms on a profitable market garden was encouraging for me. It inspired me and helped me see how making a living farming on a small scale could be possible. He showed the methods, recommended tools and gave reasons which were all helpful for me on my journey to starting my own farm. His book really lit the fire inside me.

Judith: My Mom 100%. Where I grew up in Toronto we had a big backyard where my mom grew and preserved strawberries, pears, raspberries, corn, beans, greens, all the staple vegetables — it was basically a rural Jamaican lifestyle in the middle of the city. As I got older though, my 1970’s single mom got so busy working multiple jobs, she stopped gardening. It wasn’t until I went back to Jamaica in my 20’s that I learned how growing food runs in my family, connecting with aunts and uncles whose backyard farms felt very familiar. But farming as a job was discouraged, there was a sense of shame associated with it. My family was all about education — lawyer, doctor, engineer, etc. was encouraged. I trained as a chemist. Living and travelling in southern Africa, Tanzania and West Africa later helped to strengthen my farming goals.

What does it mean to decolonize foodways and farming?

Arlene Meekis-Jung of Wawakapewin, Oji-Cree First Nation reserve.

Arlene: It’s about stepping back into our own Indigenous heritage so that we can benefit from the huge variety of traditional uses of plants and other foods. We have internalized so many colonial ideas. Current pressures and disruptions of traditional foodways, it’s a new strain of colonialism. We need to help people come out of those toxic ideas, so we can remember what our lives were like before, how we farmed or foraged and hunted, what we ate. Traditional meat is an important part of my community’s diet – we have moose, fish, caribou and make many different types of jams, jellies, syrups and traditional medicines like rosehips.

One of the elders I most respected, he didn’t like the idea of saying “food sovereignty.” He preferred terms like “food justice” or “food equality” just because “sovereign” reminded him of broken promises from the Crown. In conversation about these things, we could say “we’re going to talk about ‘food sovereignty,’ however based on input from Indigenous peoples and their elders, they prefer the term food justice.” It’s very important to acknowledge that when we’re speaking about food and farming, we’re actually speaking about equality, access, justice, all of those things — but that doesn’t always look the same for everybody. I feel this could really help people to look at the different ways people understand these terms, related with farming, food and community.

Cady & Alvis: A good way to fight the power is to support local farmers. Support your local food systems and lessen your dependence on oppressive food systems that create poverty; there is abundance in the earth for us all. Purchase a harvest share from Deeper Roots Farm if you’re into raw food, organic food, local food; pesticide-free, synthetic fertilizer-free, hate-free; black family-owned, community focussed, culturally sensitive foods — we got you. Support and join us on our journey towards farm land ownership / stewardship in Ontario.

Judith with some of Ubuntu’s early summer harvest.

How have your elders and ancestors influenced your farming and land stewardship choices?

Judith: As a mother of four and for the mothers in my community, food is a big issue. We’re always cooking, feeding, our lives revolve around food. We want to make sure our children are getting healthy, affordable food. A big motivation for farming is to have more control over what we can offer our children and the security of knowing where food is coming from. We’re also sharing and cultivating knowledge about other uses of plants, for medicine and healing. Farming collectively also sparks memory: “Oh, my mother did this,” or “My grandmother did this!” Ancestral knowledge grounds you in the knowledge “I can do this, I can provide for my family and community.” Working this way, you can give your problems to the earth and earth gives you energy back, feeds you and gives you strength to deal with all the challenges and conundrums of farming and life.

Arlene: That is how Indigenous people feel about the land as well. Even science now recognizes that working with the land and soil gives healing and benefits. As Indigenous people in my region we would not have said “farming” exactly, but we foraged and collected things and ensured that the plants in that area would be viable for the following seasons. Stewardship is a type of long term farming. We need to look at farming in a new way. There is a co-op in my area that pays youth to collect wild blueberries, then sells them in Thunder Bay and other regional places. The youth absolutely love getting out on the land, they are paid and also enjoy delicious fruit while they work. This needs to be replicated in more communities, also as a way to care for the land. I remember going out with my great grandma doing similar tasks and loving it. My great grandmother was 106 when she passed away in 1997. I was able to know what it was like in the late 1800’s before any non-Indigenous person came to our area.

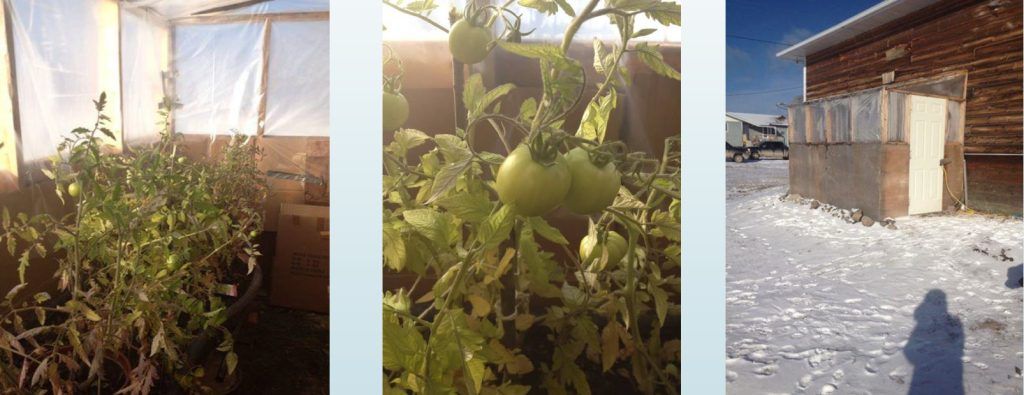

Wawakapewin tomatoes in November – an example of Arlene’s season extension efforts.

What farming setbacks have turned out to be opportunities?

Carrots getting washed at Deeper Roots Farm.

Alvis: Clay soil. It may be difficult to work with but it stores a lot of nutrients and water. We find that we don’t have to water so much in the summer compared to a sandy soil composition.

Cady: I agree. We recently expanded to a new plot with sandy loamy soil. The soil on this new plot is beautiful, however we can see the differences between them. Water retention is one of them. Our carrots for instance, which we treat fairly similarly between the plots, are germinating much better on our clay soil, likely due to the moisture.

Judith: My whole dream of being a farmer in Africa and living off the land couldn’t take root in Tanzania where I felt very connected to the land but the connection to the people was not as strong — I was always considered an outsider. It was only after coming back to Toronto in 2015, where I was born and raised, could my farm plans come to fruition in my community. It came together in the right time and place with purpose and intention. The next goal is for us to earn enough from farm sales to keep the business afloat and to support our non-profit organization, Ubuntu Community Collective.

What does growing cultural staples mean to you?

Alvis checking on the Callaloo.

Cady & Alvis: We’ve decided to focus on growing cultural staples because that is what our direct community is most interested in; they’re culturally significant for us as well. Sorrel or Hibiscus is dried and typically available in the fall to be used during Christmas as a drink. Often it is paired with rum. It represents a joyous time of the year spent with family and loved ones. Okra and Callaloo are staple dinner ingredients — they’re a reminder of home and make a warm, hearty meal. This is the cultural significance that these foods carry for us and our motivation to grow it. We think it is great and important to have a local and organic option to access these culturally important foods.

This member profile was originally published in the Fall 2022 issue of Ecological Farming in Ontario. To receive the EFAO’s member magazine, become a member of EFAO.